Psilocybin, Science, and Sacrament

A Look at the Research of and Response to the Johns Hopkins Study on Psilocybin and Mysticism

Nov 2006

Citation: Lux, Erowid eds. "Psilocybin, Science, and Sacrament." Erowid Extracts. Nov 2006;11:4-9.

See also: Psilocybin & Mystical Experience 14-Month Follow-up

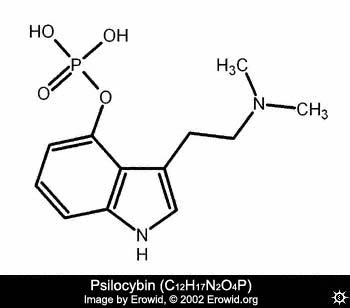

In July of this year, Johns Hopkins University announced the results of a new study published in the journal Psychopharmacology.1 In an experiment described as "landmark" and "groundbreaking", thirty-six participants were administered either psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic Psilocybe mushrooms, or methylphenidate (Ritalin), an active comparison substance, in a carefully structured environment. Thirty of those participants were administered both substances in a triple-blinded, counterbalanced procedure. According to the report, "67% of the volunteers rated the experience with psilocybin to be either the single most meaningful experience of his or her life or among the top five most meaningful experiences of his or her life."1

While many Erowid members are undoubtedly familiar with this study, and are not surprised to hear that psychedelics can occasion mystical experiences, I wanted to take a deeper look at the historical context for the research, important methodological and theoretical issues, and the reception of the story in the media. In addressing these topics I had the opportunity to speak with Bob Jesse, co-designer of the study, coauthor of the Psychopharmacology article, and chairman of the Council on Spiritual Practices (CSP).

Psychologist Abraham Maslow dedicated his career to the study of "peak-experiences" (similar to "mystical experiences" or "primary religious experiences"). Maslow describes these as being characterized by qualities such as transcendence, unity, awe, wonder, compassion, and love.2 These experiences, he believed, are commonly available, and may have inspired many religious traditions. In an essay written in 1964, Maslow observed:

Maslow may have been thinking of the 1962 Good Friday Experiment,3 in which Walter Pahnke administered capsules containing 30 mg of psilocybin to ten theology students and the active placebo nicotinic acid to ten additional students as a control. Subjects spent the duration of the experiment in a basement room of Boston University's Marsh Chapel while listening to a live broadcast of the Good Friday service being conducted in the main sanctuary upstairs. Pahnke undertook the study in order to "investigate in a systematic and scientific way the similarities and differences between experiences described by mystics and those facilitated by psychedelic drugs."3 He created a questionnaire designed to objectively measure mystical experience based on nine categories, including a sense of unity, a sense of sacredness, and deeply felt positive mood. Subjects were interviewed after the session and again after six months. Most were also interviewed 24 to 27 years later in a follow-up study conducted by Rick Doblin.4

The majority of subjects who received psilocybin scored highly on most or all of the nine categories of the mystical experience measure, while the control group scored much lower on average. Pahnke concluded that psilocybin might reliably induce mystical experience. He observed, "The results of our experiment would indicate that psilocybin (and LSD and mescaline, by analogy) are important tools for the study of the mystical state of consciousness."3

The majority of subjects who received psilocybin scored highly on most or all of the nine categories of the mystical experience measure, while the control group scored much lower on average. Pahnke concluded that psilocybin might reliably induce mystical experience. He observed, "The results of our experiment would indicate that psilocybin (and LSD and mescaline, by analogy) are important tools for the study of the mystical state of consciousness."3

Pahnke's study has been described by one expert as "perhaps the most famous study in the psychology of religion."5 Despite methodological weaknesses pointed out by Doblin and others, Pahnke's experiment is noteworthy because he examined a potential "trigger" of mystical experience, thereby paving the way for future research. As Pahnke and Maslow noted, if psychoactive compounds can trigger religious experience, it may be possible to conduct experimental investigations of these experiences. Experiments into the psychology of religion are relatively rare, with most research traditionally being descriptive rather than experimental.

Despite the widespread interest in and the promise of Pahnke's findings, little direct follow-up research has been conducted. The landscape of psychedelic research changed dramatically in the ten years after the Good Friday Experiment. A spate of new drug control laws in the mid-1960s, crowned by the U.S. Federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970, added daunting regulatory hurdles. New regulations designed to protect research participants, such as the Research Act of 1974, made it harder to experiment on human subjects.

Public backlash against the use of psychedelics during the 1960s also curbed the enthusiasm of both researchers and funders. Hallucinogens were caricatured by the mainstream media as dangerous counterculture drugs. One of the last formal clinical studies to administer hallucinogens and look for beneficial results involved Dr. Bill Richards at Spring Grove in Baltimore, who years later joined CSP as a Senior Fellow and co-authored the Hopkins study. Approved research investigating the positive aspects of scheduled psychedelics otherwise ground to a halt.

A renewal in the field began slowly in the United States in the 1990s, most notably with Rick Strassman's study of injected DMT.6 As Alexander and Ann Shulgin noted in 1997, "DMT is the only psychedelic tryptamine that has recently been taken through the Kafkaesque processes for approval for human studies (via the FDA, the DEA, and the other Health agencies of the Government) and is one of the few Schedule I drugs that is being looked at clinically in this country today."7 However, Strassman's research design touched only tangentially on the study of psychoactives and religious experience, limiting itself to "a re-examination of the human psychobiology of […] N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)". Strassman intentionally avoided mention of his mystical interests for political reasons.6 Important research was also conducted outside of the United States during that time period, including research on the religious use of ayahuasca in South America, and a series of studies on hallucinogens by Franz Vollenweider in Switzerland.

Enter the Council on Spiritual Practices in 1994. CSP's mission is "to identify and develop approaches to primary religious experience that can be used safely and effectively, and to help individuals and spiritual communities bring the insights, grace, and joy that arise from direct perception of the divine into their daily lives."8 Bob Jesse, then president of CSP, coordinated the development of CSP's research interests, including organizing several scientific meetings from 1996 through 2000 that led to and supported the Hopkins/CSP psilocybin study. "I was fortunate to have been introduced to Roland Griffiths, whose leadership as a research psychopharmacologist and curiosity as a serious meditator made him a godsend of a principle investigator", Jesse said.9 CSP staff, including Jesse and Richards, were significantly involved in the project. Fire and Earth of Erowid, who worked for CSP in the late 1990s, also assisted in early design and coordination efforts.

CSP's goal was to develop an experiment sensitive to the full range of psilocybin's reported effects, including spiritual effects. Psilocybin was selected as the research compound early on. As Jesse explains, "There are just some really good pharmacological reasons. It's a naturally occurring substance, used by humans for centuries. Modern medicine has confirmed its track record of being non-addictive and physically non-toxic, though not without behavioral, psychological, and spiritual risks. And its duration of action fit the needs of our study."

With a draft of the research protocol in hand and a team assembled, they began seeking regulatory approval from Johns Hopkins as well as the FDA and DEA. Their first step was to submit the proposal to the FDA for review. Jesse said that process went relatively smoothly: "I had heard stories of other protocols hitting hitches and stalling, but that was not our experience at all. We benefited, I'm sure, from the FDA having reviewed Strassman's protocols before us, and from Roland's long experience working with the FDA."

The experiment required approval from the DEA to work with a Schedule I substance. Because Griffiths's lab was already licensed to work with Schedule I substances, this approval was granted without complications.

Participants were recruited in Baltimore through flyers announcing a "study of states of consciousness brought about by a naturally occurring psychoactive substance used sacramentally in some cultures."1 Respondents were screened for psychological and medical health, as well as ongoing participation in a spiritual community such as a church or meditation group. Jesse explained that people with a demonstrated interest in spiritual matters might be better prepared to make sense of mystical experiences. Also, those with an active spiritual life and who participate in a spiritual community "may be in a better position to assimilate their experiences and to turn them to abiding good in their lives."

With the necessary permissions in place, the team began the experimental protocol. Great care was taken to ensure subject comfort and safety. Session monitors/guides were mental health professionals selected on the basis of their experience, reassuring demeanor, and training. Volunteer subjects met the primary guide, Bill Richards, several times prior to their first drug session to establish a comfortable rapport. During the eight hours of preparatory sessions, the guide discussed the range of effects of psilocybin (covering possible alternative states of consciousness including sensory-aesthetic, psychodynamic, psychotic, symbolic-archetypal, and mystical), and inquired about the volunteer's life history. During these sessions the monitors avoided mention of the measurement questionnaires and their categories.

The final preparatory session was held in the same room used for the experimental sessions in order to allow volunteers to become familiar with the room and "test drive" the couch with headphones and eyeshades. This preparatory session also covered practical matters, such as how blood pressure monitoring would occur and how to deal with possible nausea or trips to the restroom.

The study was triple-blind, in that neither researchers, nor monitors, nor volunteers knew if the volunteers were receiving psilocybin or a control. Further, neither monitors nor volunteers knew which control drug would be used. They had been given a list of possible control drugs, including an inactive placebo, low-dose psilocybin, dextromethorphan, codeine, and eight other drugs, in order to make it difficult to know whether the session was a control session even after psychoactive effects began.

The psilocybin dose was set at 30 mg per 70 kg body weight, considered by researchers a "high safe dose" able to induce a strong experience.1 Methylphenidate (40 mg per 70 kg) was selected as the comparison substance (an "active placebo"), as its somewhat similar physical and mood-altering effects could realistically be mistaken for psilocybin by drug-naïve participants. The journal article describes the experimental sessions as follows:

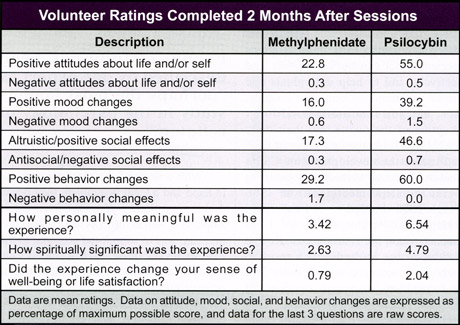

Blood pressure and pulse were taken unobtrusively, and seven hours after the session began, subjects were administered five carefully-selected questionnaires. Two of these measures were based on those that Pahnke and Strassman developed for their work with psilocybin and DMT, respectively. One questionnaire, the Hood Mysticism Scale, was originally developed to evaluate mystical experiences and had not previously been used in psychoactive drug research. Two months after the first session, a series of follow-up questionnaires were administered to gather data about longterm effects. A second session was then conducted in which subjects who had previously received the methylphenidate now received psilocybin, and vice versa.note 1 An additional follow-up assessment was conducted two months later using the same set of questionnaires.

One novel element of the study design was that each subject designated three adults who would be in close contact with them in the months following the experiment. During the two-month follow-up, these "community observers" were administered questionnaires by telephone that were designed to track observable, lasting changes in the subjects. Community observers were used to corroborate self-reports by the participants and to keep an eye on their mental well-being.

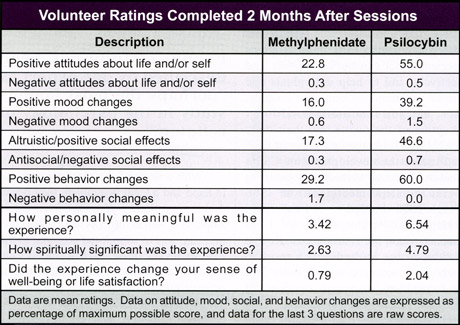

Psilocybin appeared to be effective in generating mystical experiences as measured by the study instruments. Griffiths et al. reported that "22 of the total group of 36 volunteers had a 'complete' mystical experience after psilocybin […] while only 4 of 36 did so after methylphenidate". In the two-month follow-up, large numbers of respondents ascribed great significance to the experimental sessions: "Thirty-three percent of the volunteers rated the psilocybin experience as being the single most spiritually significant experience of his or her life, with an additional 38% rating it to be among the top five most spiritually significant experiences." This contrasts starkly with the experience of the control condition. "After methylphenidate, in contrast, 8% of volunteers rated the experience to be among the top five (but not the single most) spiritually significant experiences", and none rated it as the single-most significant experience.1

About 30% of subjects reported "strong" or "extreme" feelings of fear during the experiment. Two of the subjects likened their experience to "being in a war", and three indicated "they would never wish to repeat an experience like that again." Experiences of fear were most often confined to limited portions of the experimental session.

While similar in design to the Good Friday experiment, the Hopkins study amplified Pahnke's findings in several important aspects. In the former, the double-blind was broken as soon as the effects of the psilocybin became apparent. Because it quickly became clear which subjects had received psilocybin, they may have been treated differently by other subjects and monitors, potentially influencing the results of the experiment. In contrast, the Griffiths study was much more rigorous about preserving the integrity of the triple-blind: methylphenidate so well mimicked the experimental condition that even expert monitors mistakenly believed subjects had been given psilocybin during 23% of the control sessions. This design minimized risks that monitors would introduce bias through their own actions.

A common issue with research into spiritual experience is that expectation and preparation may hinder measurement validity. This is similar to the well-known "set and setting" aspect of psychedelic drugs, where factors such as the background of the subject and the context of the experience can strongly influence the experience and its interpretation. Simply put, subjects expecting a mystical experience may be more likely to have one.

One critic of the study, Dr. Rosamond Rhodes of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, has argued that the expectancy effects damaged the validity of the results. Dr. Rhodes contended, "After each administration of the drug, they gave people the same set of questionnaires. As you ask people these questions each time, you are also directing them to focus that way […] You are encouraging people to close their eyes, to concentrate, and you are not just doing this to regular people but to people who are religiously inclined. They are suggesting that this is what you are going to get from the drug, so they find a great deal of that sort of response, particularly to the drug psilocybin."10

Jesse responded to Rhodes's criticism by pointing out that the study was designed specifically to control for expectations. As Dr. Charles Schuster noted in his commentary, "These participants were well-prepared for the psilocybin experience by an experienced monitor, who expressly stated that psilocybin might produce increased personal awareness and insight. However, it is clear that the effects of psilocybin were more than expectancy effects because the active drug control condition (40 mg of methylphenidate) did not produce similar effects on ratings of significance or on measures of spirituality, positive attitude, or behavior."11

It is nonetheless important to note that the design of the experiment limits the degree to which its results can be generalized. Participants were selected partially for their involvement in spiritual practices and prepared for a range of effects that included mystical experiences. Moreover, some of the outcome measures clearly targeted mystical experience. As the researchers wrote, "it seems plausible that the religious or spiritual interest of the participants may have increased the likelihood that the psilocybin experience would be interpreted as having substantial spiritual significance and personal meaning."1 As Jesse observed, it remains to be seen how strong the spiritual effects would be in other populations, such as volunteers without a demonstrated spiritual inclination. Despite these qualifications, the study did provide strong evidence that, within its parameters, psilocybin was effective in catalyzing highly meaningful mystical experiences.

The results of the experiment were announced on July 11, 2006. Johns Hopkins issued a press release and, in an unusual move, their website hosted the complete Psychopharmacology article and accompanying commentaries by four distinguished experts, including Dr. Herbert Kleber, former Deputy Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. The university also released a series of questions and answers about the study by Dr. Griffiths.

The Associated Press wire was widely circulated, but many news sources wrote their own more detailed articles, including ABC News, The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, The Japan Times, New Scientist, and Forbes, among others. The news was featured as a top story on CNN.com for more than a day, and as a link on their science page for several additional days. The accuracy of media reports varied widely. Minor inaccuracies were common common even in carefully-written pieces. For example, several articles failed to distinguish between informal self-reports by subjects and the results of standardized measurements. The AP report claimed that, "Twenty-two of the 36 volunteers reported having a 'complete' mystical experience, compared to four of those getting methylphenidate."12 This implies that those subjects merely said something like, "I had a mystical experience", when in fact, they "met criteria for a 'full mystical experience' as measured by established psychological scales",13 and may never have used the term "mystical experience" themselves.

Some news outlets emphasized the anxiety and fear aspects, giving the impression that volunteers experienced only extreme fear during the session. For example, The Wall Street Journal reported that "in 30% of the cases, the drug provoked harrowing experiences dominated by fear and paranoia",14 omitting the fact that Griffiths et al. reported that "no volunteer rated the experience as having decreased their sense of well being or life satisfaction."1 The Baltimore Sun began their article with, "The hallucinogen in the 'magic mushrooms' of the 1960s can produce terror, paranoia and schizophrenia, but it can also spark a religious and mystical experience that leaves the user feeling kinder and happier".15

The Japan Times article was particularly amusing, and offered this description of the study's findings: "New research shows that for some of those who revel at music festivals like the Fuji Rock Festival in Japan, the most spiritually significant thing they will have ever done was taking a psilocybin trip while soaking up the sounds."16

Many reporters remarked with varying degrees of seriousness that this study corroborates what the 1960s counterculture knew all along: that spiritual insight may be gained through the reflective use of psychoactive substances. But this was often reported with a wink by including humorous references to Timothy Leary, hippies, and tie-dyes. Take, for example, the ABC News article titled "Tripping Out": "This may come as no surprise to the flower children of the 1960s, but in one of the few controlled human studies of a known illegal hallucinogen, the active ingredient in 'sacred mushrooms' created what researchers are describing as deep mystical experiences that left many of the study participants with a long lasting sense of well-being."10 The article's title and tone suggest that the very idea of finding spiritual insight through the use of psychedelics is silly.

Many reporters remarked with varying degrees of seriousness that this study corroborates what the 1960s counterculture knew all along: that spiritual insight may be gained through the reflective use of psychoactive substances. But this was often reported with a wink by including humorous references to Timothy Leary, hippies, and tie-dyes. Take, for example, the ABC News article titled "Tripping Out": "This may come as no surprise to the flower children of the 1960s, but in one of the few controlled human studies of a known illegal hallucinogen, the active ingredient in 'sacred mushrooms' created what researchers are describing as deep mystical experiences that left many of the study participants with a long lasting sense of well-being."10 The article's title and tone suggest that the very idea of finding spiritual insight through the use of psychedelics is silly.

Yet many of the articles also conveyed a sense of fascination. Despite minor errors, most of the coverage was quite accurate, balanced, and surprisingly positive. Credit for this goes in part to the research team for inviting critical feedback on the study design from outside experts before the research began.

Experimental research in the psychology of religion has received increased interest in recent years.17 The Griffiths study has broad implications for future research as it offers a robust experimental model that may promote further studies not only on the neurochemistry of hallucinogens, but on the mystical experience itself.

Indeed, the use of the term "mystical experience" is provocative and controversial. Very little is known about how psilocybin produces its effects, yet the Hopkins researchers concluded that, "When administered under supportive conditions, psilocybin occasioned experiences similar to spontaneously occurring mystical experiences."1 Similar in terms of the effects the researchers measured, perhaps; but many mystical traditions insist that they deal with phenomena that cannot be described. This is reminiscent of the famous opening lines of the Tao Te Ching, "The Way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way." Is it possible to study or measure such experiences?

"Any dialog around that question would be strongly contingent on what it is that those quantitative measures purport to measure", Jesse answers. "Mystics tell us that the core experience can't be pinned down in words. But can't we report what we find nearby? It's like the sun–if you try to stare at the sun itself you probably won't glean much to say except, 'bright!'. But you can make more detailed observations about the halo around the sun, and turning around, you can see its effects on the world around you." In a similar sense, he argues, we can measure the effects of a religious experience without having to fully characterize the experience itself. "Notice," he says, "that we did not even try."

According to subjects' scores on the Hood Mysticism Scale--a questionnaire originally developed for the study of non-drug-related religious experiences--the experiences of study participants were indistinguishable from more conventional forms of mystical experiences. However, measurement may not be the final word on mystical experience. How do we distinguish between a "powerful" experience and a "mystical" experience? Sigmund Freud argued in The Future of an Illusion and Civilization and its Discontents that what people describe as a mystical experience is in fact a recollection of an infantile state of unity with the mother. Freud argues that when people report a mystical experience, they are in fact experiencing a neurotic episode.

I put the question to Jesse directly: Do you think that the subjects of this study experienced an actual primary religious experience? "Wisdom has it," he replied, "that it's the consequences of a reported religious experience that gives the best evidence of its authenticity. 'By their fruits shall ye know them.' This research gave us data, some from self-reports and some from community observers, suggesting that some volunteers became kinder after their psilocybin experience. Would psilocybin always occasion primary religious experience? Of course not. Can it sometimes? This study gives us good reason to say 'yes', and good reason to look further into what factors account for varying consequences."

However we interpret the findings, the response to this research may be a useful barometer to measure modern society's relationship to psychedelics. It is striking that the story received such widespread coverage not just among specialists, but within society at large. Perhaps questions raised by altered states of consciousness have greater social relevance than most would expect.

This research has provided a solid mooring for discussion in the face of entrenched skepticism toward the notion that psychedelics may be profound tools of self-discovery. The conversation around psychoactives is easily distorted on both sides. Over-zealous advocates may minimize risks, while over-zealous critics may exaggerate them. The study is significant for contributing concrete data to the conversation, although it may ultimately prove impossible for opposing sides to agree on one interpretation.

In a similar vein, Jesse noted: "The study may help people to better understand different psychoactives by their differing properties and differing risks, breaking down overly-broad categories. I also hope it calls more attention to primary religious experience, whether occasioned by psychoactives or through other means."

While the long-term consequences of this study have yet to be seen, one can speculate that where well-respected researchers lead, others will more easily follow. The rigorous language of science can encourage people to listen to and consider issues they might otherwise dismiss. Now that recent investigations have begun to legitimize the study of sacramental psychedelic use, the door stands open to further research in the same vein. Indeed, it is already underway. •

I. Introduction

In July of this year, Johns Hopkins University announced the results of a new study published in the journal Psychopharmacology.1 In an experiment described as "landmark" and "groundbreaking", thirty-six participants were administered either psilocybin, the active ingredient in hallucinogenic Psilocybe mushrooms, or methylphenidate (Ritalin), an active comparison substance, in a carefully structured environment. Thirty of those participants were administered both substances in a triple-blinded, counterbalanced procedure. According to the report, "67% of the volunteers rated the experience with psilocybin to be either the single most meaningful experience of his or her life or among the top five most meaningful experiences of his or her life."1

While many Erowid members are undoubtedly familiar with this study, and are not surprised to hear that psychedelics can occasion mystical experiences, I wanted to take a deeper look at the historical context for the research, important methodological and theoretical issues, and the reception of the story in the media. In addressing these topics I had the opportunity to speak with Bob Jesse, co-designer of the study, coauthor of the Psychopharmacology article, and chairman of the Council on Spiritual Practices (CSP).

II. Back in the Day

Psychologist Abraham Maslow dedicated his career to the study of "peak-experiences" (similar to "mystical experiences" or "primary religious experiences"). Maslow describes these as being characterized by qualities such as transcendence, unity, awe, wonder, compassion, and love.2 These experiences, he believed, are commonly available, and may have inspired many religious traditions. In an essay written in 1964, Maslow observed:

In the last few years it has become quite clear that certain drugs called "psychedelic," especially LSD and psilocybin, give us some possibility of control in this realm of peak-experiences. It looks as if these drugs often produce peak-experiences in the right people under the right circumstances, so that perhaps we needn't wait for them to occur by good fortune. Perhaps we can actually produce a private personal peak-experience under observation and whenever we wish under religious or nonreligious circumstances.2

Maslow may have been thinking of the 1962 Good Friday Experiment,3 in which Walter Pahnke administered capsules containing 30 mg of psilocybin to ten theology students and the active placebo nicotinic acid to ten additional students as a control. Subjects spent the duration of the experiment in a basement room of Boston University's Marsh Chapel while listening to a live broadcast of the Good Friday service being conducted in the main sanctuary upstairs. Pahnke undertook the study in order to "investigate in a systematic and scientific way the similarities and differences between experiences described by mystics and those facilitated by psychedelic drugs."3 He created a questionnaire designed to objectively measure mystical experience based on nine categories, including a sense of unity, a sense of sacredness, and deeply felt positive mood. Subjects were interviewed after the session and again after six months. Most were also interviewed 24 to 27 years later in a follow-up study conducted by Rick Doblin.4

The majority of subjects who received psilocybin scored highly on most or all of the nine categories of the mystical experience measure, while the control group scored much lower on average. Pahnke concluded that psilocybin might reliably induce mystical experience. He observed, "The results of our experiment would indicate that psilocybin (and LSD and mescaline, by analogy) are important tools for the study of the mystical state of consciousness."3

The majority of subjects who received psilocybin scored highly on most or all of the nine categories of the mystical experience measure, while the control group scored much lower on average. Pahnke concluded that psilocybin might reliably induce mystical experience. He observed, "The results of our experiment would indicate that psilocybin (and LSD and mescaline, by analogy) are important tools for the study of the mystical state of consciousness."3Pahnke's study has been described by one expert as "perhaps the most famous study in the psychology of religion."5 Despite methodological weaknesses pointed out by Doblin and others, Pahnke's experiment is noteworthy because he examined a potential "trigger" of mystical experience, thereby paving the way for future research. As Pahnke and Maslow noted, if psychoactive compounds can trigger religious experience, it may be possible to conduct experimental investigations of these experiences. Experiments into the psychology of religion are relatively rare, with most research traditionally being descriptive rather than experimental.

III. Hiatus

Despite the widespread interest in and the promise of Pahnke's findings, little direct follow-up research has been conducted. The landscape of psychedelic research changed dramatically in the ten years after the Good Friday Experiment. A spate of new drug control laws in the mid-1960s, crowned by the U.S. Federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970, added daunting regulatory hurdles. New regulations designed to protect research participants, such as the Research Act of 1974, made it harder to experiment on human subjects.

Public backlash against the use of psychedelics during the 1960s also curbed the enthusiasm of both researchers and funders. Hallucinogens were caricatured by the mainstream media as dangerous counterculture drugs. One of the last formal clinical studies to administer hallucinogens and look for beneficial results involved Dr. Bill Richards at Spring Grove in Baltimore, who years later joined CSP as a Senior Fellow and co-authored the Hopkins study. Approved research investigating the positive aspects of scheduled psychedelics otherwise ground to a halt.

A renewal in the field began slowly in the United States in the 1990s, most notably with Rick Strassman's study of injected DMT.6 As Alexander and Ann Shulgin noted in 1997, "DMT is the only psychedelic tryptamine that has recently been taken through the Kafkaesque processes for approval for human studies (via the FDA, the DEA, and the other Health agencies of the Government) and is one of the few Schedule I drugs that is being looked at clinically in this country today."7 However, Strassman's research design touched only tangentially on the study of psychoactives and religious experience, limiting itself to "a re-examination of the human psychobiology of […] N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)". Strassman intentionally avoided mention of his mystical interests for political reasons.6 Important research was also conducted outside of the United States during that time period, including research on the religious use of ayahuasca in South America, and a series of studies on hallucinogens by Franz Vollenweider in Switzerland.

IV. An Experiment is Born

Enter the Council on Spiritual Practices in 1994. CSP's mission is "to identify and develop approaches to primary religious experience that can be used safely and effectively, and to help individuals and spiritual communities bring the insights, grace, and joy that arise from direct perception of the divine into their daily lives."8 Bob Jesse, then president of CSP, coordinated the development of CSP's research interests, including organizing several scientific meetings from 1996 through 2000 that led to and supported the Hopkins/CSP psilocybin study. "I was fortunate to have been introduced to Roland Griffiths, whose leadership as a research psychopharmacologist and curiosity as a serious meditator made him a godsend of a principle investigator", Jesse said.9 CSP staff, including Jesse and Richards, were significantly involved in the project. Fire and Earth of Erowid, who worked for CSP in the late 1990s, also assisted in early design and coordination efforts.

CSP's goal was to develop an experiment sensitive to the full range of psilocybin's reported effects, including spiritual effects. Psilocybin was selected as the research compound early on. As Jesse explains, "There are just some really good pharmacological reasons. It's a naturally occurring substance, used by humans for centuries. Modern medicine has confirmed its track record of being non-addictive and physically non-toxic, though not without behavioral, psychological, and spiritual risks. And its duration of action fit the needs of our study."

"Pahnke's study has been described by one expert as 'perhaps the most famous study in the psychology of religion.'"

The experiment required approval from the DEA to work with a Schedule I substance. Because Griffiths's lab was already licensed to work with Schedule I substances, this approval was granted without complications.

Participants were recruited in Baltimore through flyers announcing a "study of states of consciousness brought about by a naturally occurring psychoactive substance used sacramentally in some cultures."1 Respondents were screened for psychological and medical health, as well as ongoing participation in a spiritual community such as a church or meditation group. Jesse explained that people with a demonstrated interest in spiritual matters might be better prepared to make sense of mystical experiences. Also, those with an active spiritual life and who participate in a spiritual community "may be in a better position to assimilate their experiences and to turn them to abiding good in their lives."

V. Lift-Off

With the necessary permissions in place, the team began the experimental protocol. Great care was taken to ensure subject comfort and safety. Session monitors/guides were mental health professionals selected on the basis of their experience, reassuring demeanor, and training. Volunteer subjects met the primary guide, Bill Richards, several times prior to their first drug session to establish a comfortable rapport. During the eight hours of preparatory sessions, the guide discussed the range of effects of psilocybin (covering possible alternative states of consciousness including sensory-aesthetic, psychodynamic, psychotic, symbolic-archetypal, and mystical), and inquired about the volunteer's life history. During these sessions the monitors avoided mention of the measurement questionnaires and their categories.

The final preparatory session was held in the same room used for the experimental sessions in order to allow volunteers to become familiar with the room and "test drive" the couch with headphones and eyeshades. This preparatory session also covered practical matters, such as how blood pressure monitoring would occur and how to deal with possible nausea or trips to the restroom.

The study was triple-blind, in that neither researchers, nor monitors, nor volunteers knew if the volunteers were receiving psilocybin or a control. Further, neither monitors nor volunteers knew which control drug would be used. They had been given a list of possible control drugs, including an inactive placebo, low-dose psilocybin, dextromethorphan, codeine, and eight other drugs, in order to make it difficult to know whether the session was a control session even after psychoactive effects began.

The psilocybin dose was set at 30 mg per 70 kg body weight, considered by researchers a "high safe dose" able to induce a strong experience.1 Methylphenidate (40 mg per 70 kg) was selected as the comparison substance (an "active placebo"), as its somewhat similar physical and mood-altering effects could realistically be mistaken for psilocybin by drug-naïve participants. The journal article describes the experimental sessions as follows:

The 8-h drug sessions were conducted in an aesthetic livingroom- like environment designed specifically for the study. Two monitors were present with a single participant throughout the session. For most of the time during the session, the participant was encouraged to lie down on the couch, use an eye mask to block external visual distraction, and use headphones through which a classical music program was played. […] The participants were encouraged to focus their attention on their inner experiences throughout the session. If a participant reported significant fear or anxiety, the monitors provided reassurance verbally or physically (e.g., with a supportive touch to the hand or shoulder).1

Blood pressure and pulse were taken unobtrusively, and seven hours after the session began, subjects were administered five carefully-selected questionnaires. Two of these measures were based on those that Pahnke and Strassman developed for their work with psilocybin and DMT, respectively. One questionnaire, the Hood Mysticism Scale, was originally developed to evaluate mystical experiences and had not previously been used in psychoactive drug research. Two months after the first session, a series of follow-up questionnaires were administered to gather data about longterm effects. A second session was then conducted in which subjects who had previously received the methylphenidate now received psilocybin, and vice versa.note 1 An additional follow-up assessment was conducted two months later using the same set of questionnaires.

One novel element of the study design was that each subject designated three adults who would be in close contact with them in the months following the experiment. During the two-month follow-up, these "community observers" were administered questionnaires by telephone that were designed to track observable, lasting changes in the subjects. Community observers were used to corroborate self-reports by the participants and to keep an eye on their mental well-being.

VI. Results

Psilocybin appeared to be effective in generating mystical experiences as measured by the study instruments. Griffiths et al. reported that "22 of the total group of 36 volunteers had a 'complete' mystical experience after psilocybin […] while only 4 of 36 did so after methylphenidate". In the two-month follow-up, large numbers of respondents ascribed great significance to the experimental sessions: "Thirty-three percent of the volunteers rated the psilocybin experience as being the single most spiritually significant experience of his or her life, with an additional 38% rating it to be among the top five most spiritually significant experiences." This contrasts starkly with the experience of the control condition. "After methylphenidate, in contrast, 8% of volunteers rated the experience to be among the top five (but not the single most) spiritually significant experiences", and none rated it as the single-most significant experience.1

About 30% of subjects reported "strong" or "extreme" feelings of fear during the experiment. Two of the subjects likened their experience to "being in a war", and three indicated "they would never wish to repeat an experience like that again." Experiences of fear were most often confined to limited portions of the experimental session.

While similar in design to the Good Friday experiment, the Hopkins study amplified Pahnke's findings in several important aspects. In the former, the double-blind was broken as soon as the effects of the psilocybin became apparent. Because it quickly became clear which subjects had received psilocybin, they may have been treated differently by other subjects and monitors, potentially influencing the results of the experiment. In contrast, the Griffiths study was much more rigorous about preserving the integrity of the triple-blind: methylphenidate so well mimicked the experimental condition that even expert monitors mistakenly believed subjects had been given psilocybin during 23% of the control sessions. This design minimized risks that monitors would introduce bias through their own actions.

VII. Expectancy Questions

"Psilocybin appeared to be effective in generating mystical experiences as measured by the study instruments."

One critic of the study, Dr. Rosamond Rhodes of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, has argued that the expectancy effects damaged the validity of the results. Dr. Rhodes contended, "After each administration of the drug, they gave people the same set of questionnaires. As you ask people these questions each time, you are also directing them to focus that way […] You are encouraging people to close their eyes, to concentrate, and you are not just doing this to regular people but to people who are religiously inclined. They are suggesting that this is what you are going to get from the drug, so they find a great deal of that sort of response, particularly to the drug psilocybin."10

Jesse responded to Rhodes's criticism by pointing out that the study was designed specifically to control for expectations. As Dr. Charles Schuster noted in his commentary, "These participants were well-prepared for the psilocybin experience by an experienced monitor, who expressly stated that psilocybin might produce increased personal awareness and insight. However, it is clear that the effects of psilocybin were more than expectancy effects because the active drug control condition (40 mg of methylphenidate) did not produce similar effects on ratings of significance or on measures of spirituality, positive attitude, or behavior."11

It is nonetheless important to note that the design of the experiment limits the degree to which its results can be generalized. Participants were selected partially for their involvement in spiritual practices and prepared for a range of effects that included mystical experiences. Moreover, some of the outcome measures clearly targeted mystical experience. As the researchers wrote, "it seems plausible that the religious or spiritual interest of the participants may have increased the likelihood that the psilocybin experience would be interpreted as having substantial spiritual significance and personal meaning."1 As Jesse observed, it remains to be seen how strong the spiritual effects would be in other populations, such as volunteers without a demonstrated spiritual inclination. Despite these qualifications, the study did provide strong evidence that, within its parameters, psilocybin was effective in catalyzing highly meaningful mystical experiences.

VIII. The Story Breaks

The results of the experiment were announced on July 11, 2006. Johns Hopkins issued a press release and, in an unusual move, their website hosted the complete Psychopharmacology article and accompanying commentaries by four distinguished experts, including Dr. Herbert Kleber, former Deputy Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy. The university also released a series of questions and answers about the study by Dr. Griffiths.

"Despite minor errors, most of the [media] coverage was quite accurate, balanced, and surprisingly positive."

Some news outlets emphasized the anxiety and fear aspects, giving the impression that volunteers experienced only extreme fear during the session. For example, The Wall Street Journal reported that "in 30% of the cases, the drug provoked harrowing experiences dominated by fear and paranoia",14 omitting the fact that Griffiths et al. reported that "no volunteer rated the experience as having decreased their sense of well being or life satisfaction."1 The Baltimore Sun began their article with, "The hallucinogen in the 'magic mushrooms' of the 1960s can produce terror, paranoia and schizophrenia, but it can also spark a religious and mystical experience that leaves the user feeling kinder and happier".15

The Japan Times article was particularly amusing, and offered this description of the study's findings: "New research shows that for some of those who revel at music festivals like the Fuji Rock Festival in Japan, the most spiritually significant thing they will have ever done was taking a psilocybin trip while soaking up the sounds."16

Many reporters remarked with varying degrees of seriousness that this study corroborates what the 1960s counterculture knew all along: that spiritual insight may be gained through the reflective use of psychoactive substances. But this was often reported with a wink by including humorous references to Timothy Leary, hippies, and tie-dyes. Take, for example, the ABC News article titled "Tripping Out": "This may come as no surprise to the flower children of the 1960s, but in one of the few controlled human studies of a known illegal hallucinogen, the active ingredient in 'sacred mushrooms' created what researchers are describing as deep mystical experiences that left many of the study participants with a long lasting sense of well-being."10 The article's title and tone suggest that the very idea of finding spiritual insight through the use of psychedelics is silly.

Many reporters remarked with varying degrees of seriousness that this study corroborates what the 1960s counterculture knew all along: that spiritual insight may be gained through the reflective use of psychoactive substances. But this was often reported with a wink by including humorous references to Timothy Leary, hippies, and tie-dyes. Take, for example, the ABC News article titled "Tripping Out": "This may come as no surprise to the flower children of the 1960s, but in one of the few controlled human studies of a known illegal hallucinogen, the active ingredient in 'sacred mushrooms' created what researchers are describing as deep mystical experiences that left many of the study participants with a long lasting sense of well-being."10 The article's title and tone suggest that the very idea of finding spiritual insight through the use of psychedelics is silly. Yet many of the articles also conveyed a sense of fascination. Despite minor errors, most of the coverage was quite accurate, balanced, and surprisingly positive. Credit for this goes in part to the research team for inviting critical feedback on the study design from outside experts before the research began.

IX. The Science of Spirit

Experimental research in the psychology of religion has received increased interest in recent years.17 The Griffiths study has broad implications for future research as it offers a robust experimental model that may promote further studies not only on the neurochemistry of hallucinogens, but on the mystical experience itself.

Indeed, the use of the term "mystical experience" is provocative and controversial. Very little is known about how psilocybin produces its effects, yet the Hopkins researchers concluded that, "When administered under supportive conditions, psilocybin occasioned experiences similar to spontaneously occurring mystical experiences."1 Similar in terms of the effects the researchers measured, perhaps; but many mystical traditions insist that they deal with phenomena that cannot be described. This is reminiscent of the famous opening lines of the Tao Te Ching, "The Way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way." Is it possible to study or measure such experiences?

"Any dialog around that question would be strongly contingent on what it is that those quantitative measures purport to measure", Jesse answers. "Mystics tell us that the core experience can't be pinned down in words. But can't we report what we find nearby? It's like the sun–if you try to stare at the sun itself you probably won't glean much to say except, 'bright!'. But you can make more detailed observations about the halo around the sun, and turning around, you can see its effects on the world around you." In a similar sense, he argues, we can measure the effects of a religious experience without having to fully characterize the experience itself. "Notice," he says, "that we did not even try."

According to subjects' scores on the Hood Mysticism Scale--a questionnaire originally developed for the study of non-drug-related religious experiences--the experiences of study participants were indistinguishable from more conventional forms of mystical experiences. However, measurement may not be the final word on mystical experience. How do we distinguish between a "powerful" experience and a "mystical" experience? Sigmund Freud argued in The Future of an Illusion and Civilization and its Discontents that what people describe as a mystical experience is in fact a recollection of an infantile state of unity with the mother. Freud argues that when people report a mystical experience, they are in fact experiencing a neurotic episode.

"Perhaps questions raised by altered states of consciousness have greater social relevance than most would expect."

X. Implications

However we interpret the findings, the response to this research may be a useful barometer to measure modern society's relationship to psychedelics. It is striking that the story received such widespread coverage not just among specialists, but within society at large. Perhaps questions raised by altered states of consciousness have greater social relevance than most would expect.

This research has provided a solid mooring for discussion in the face of entrenched skepticism toward the notion that psychedelics may be profound tools of self-discovery. The conversation around psychoactives is easily distorted on both sides. Over-zealous advocates may minimize risks, while over-zealous critics may exaggerate them. The study is significant for contributing concrete data to the conversation, although it may ultimately prove impossible for opposing sides to agree on one interpretation.

In a similar vein, Jesse noted: "The study may help people to better understand different psychoactives by their differing properties and differing risks, breaking down overly-broad categories. I also hope it calls more attention to primary religious experience, whether occasioned by psychoactives or through other means."

While the long-term consequences of this study have yet to be seen, one can speculate that where well-respected researchers lead, others will more easily follow. The rigorous language of science can encourage people to listen to and consider issues they might otherwise dismiss. Now that recent investigations have begun to legitimize the study of sacramental psychedelic use, the door stands open to further research in the same vein. Indeed, it is already underway. •

References #

- Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. "Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual experience". Psychopharmacology. 2006;187(3):268–83.

- Maslow A. Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences. Viking Penguin. 1964.

- Pahnke W. "Drugs and mysticism". Int J Parapsychology. 1966;8(2):295-313.

- Doblin R. "Pahnke's 'Good Friday Experiment': A long-term follow-up and methodological critique". J Transpersonal Psych. 1991;23(1):1–28.

- Hood RW Jr, Spilka B, Hunsberger B, et al. The Psychology of Religion. The Guilford Press. 1996. pg. 256.

- Strassman R. DMT: The Spirit Molecule. Park Street Press. 2001.

- Shulgin AT, Shulgin A. TiHKAL; The Continuation. Transform Press. 1997.

- Council on Spiritual Practices. "Council on Spiritual Practices. CSP.org. Accessed Oct 2006; http://www.csp.org.

- Jesse R. Interviewed for this article. Sep 2006.

- Victory J, Radhakrishnan B, Carter A. "Tripping Out: Scientists Study Mystical Effects of Mushrooms". ABC News. Jul 11, 2006. Accessed Sep 2006; http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=2174998.

- Schuster CR. "Commentary on: Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences […]". Psychopharmacology (Berl). Jul 7 2006;187(3):284-92.

- AP. "Mystic mushrooms spawn magic event: Findings could lead to treatments for addiction, depression". Associated Press. Jul 11, 2006.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. "Hopkins Scientists Show Hallucinogen in Mushrooms Creates Universal 'Mystical' Experience". Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed Sep 2006; http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/Press_releases/2006/07_11_06.html.

- Winslow R. "Go Ask Alice: Mushroom Drug Is Studied Anew". Wall Street Journal. Jul 11, 2006. Accessed Oct 2006; http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB115258280486902994-AkOJkdepEq_uYKdjxsfSC_cKVtw_20060809.html?mod=tff_main_tff_top.

- Emery C. "Hallucinogen Found To Have Diverse Effects". Baltimore Sun. Jul 11, 2006. Accessed Oct 2006; http://cannabisnews.com/news/21/thread21987.shtml.

- Hooper R. "Guinea Pigs Hail 'Mystical Experience'". Japan Times. Jul 12, 2006. Accessed Oct 2006; http://search.japantimes.co.jp/member/member.html?appURL=fe20060712rh.html.

- Austin J. Zen-Brain Reflections. MIT Press. 2006.

Notes #

Revision History #