Through the Four-Color Doors of Perception

Psychedelic Gems of the Comic Book Genre

Nov 2012

Citation: Bey D. "Through the Four-Color Doors of Perception: Psychedelic Gems of the Comic Book Genre". Erowid Extracts. Nov 2012;23:22-23. Online edition: Erowid.org/library/review/review_article7.shtml

There's something essentially trippy about comic books. A medium in which words and images converge is going to be at least somewhat psychedelic. Reading comics engenders a novel mode of cognitive operation, one capable of generating mental events entirely different from those derived through either reading pure text or absorbing moving image alone.

Furthermore, comic book superheroes are the closest thing contemporary culture has to living mythology, and those with pretensions to modern shamanism will tend to share traits with them. Ever since Ken Kesey began dressing up as his childhood hero, Captain Marvel, and encouraging his entourage to follow suit, the counterculture has continually reenacted the primal superhero traditions of outrageous costumes, taking on a totemic moniker, and cultivating the use of unusual abilities and extraordinary perceptions.

Here are some gems from the field of sequential visual art that focus on the exploration of alternative consciousness.

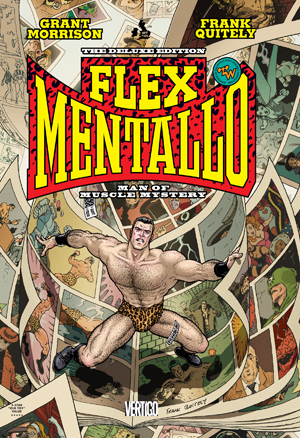

Don't let the leopard-print short-shorts fool you! Four-part comic book miniseries Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery (reprinted at long last in a handsome hardcover "deluxe" edition) is one of the most sophisticated representations of a drug trip ever written or drawn.

In a world on the brink of collapse, the last of the comic book superheroes--a half-naked cartoon strongman with psychic muscles struggles to solve the mystery of his long-vanished comrade's uncanny disappearance.

At the same time in an alternate reality, an unnamed rock singer is dying of a drug overdose in the rain. He's taken everything in the house, including quite a bit of LSD, and he's talking on a mobile phone to the unseen voice on the other end of a suicide prevention hotline. All he wants to talk about are comic books.

Meanwhile, in a third version of reality, a legion of all-powerful super-beings faced with inescapable annihilation devise a plan to survive death by projecting themselves into another universe as fictional characters.

Naturally, as the story progresses the walls between worlds begin to break down, culminating in collision with Total Reality and emotional catharsis in which there are "no more barriers between the real and the imaginary". If the world of psychedelic comic books dished out awards, Flex Mentallo would win "Best Comic Book Depiction of an Acid Trip" and "Best Narrative Depiction of Successful Psychedelic Therapy". Insofar as Flex Mentallo is about the use of non-ordinary states of consciousness to heal psychic trauma and transmute pain and fear into wonder, it is a story about psychedelic psychotherapy. Insofar as the structure of the miniseries mirrors and discusses the history of superhero comic books, Flex Mentallo is, well... about comic books.

For years Scottish author Grant Morrison has been using the medium of superhero comics to saturate his readership with an all-out assault on ordinary reality. His comics read like catalogs of ultra-hip esoterica and cutting-edge visionary speculation. Additionally, Frank Quitely's illustrations for Flex Mentallo are the clearest, most precise realizations of fantastic reality since Winsor McKay's Little Nemo in Slumberland. Together they cut an astounding swath across the limits of what is conventionally possible to represent, telling a story that's both formally intriguing and genuinely moving.

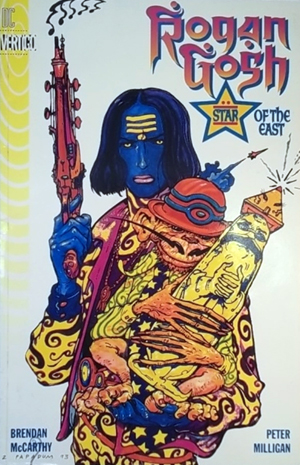

Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream... into the sitar-fantastic surrealist wonderland of Rogan Gosh, where multi-cephalic Hindu gods, karma-surfing superheroes and long-dead Orientalist writers crash headlong into the bleak drizzle of London suburbia.

Rogan Gosh, written by UK comic book bad-boy Peter Milligan, is either the story of the eponymous "Karmanaut" in his struggle to free himself from the illusionary machinations of the villainous Soma Swami--or--it's what happens to curry-house waiter Raju and boorish lout Dean after the goddess Kali rips their heads off--or--it's the opium dream of a disgraced Rudyard Kipling--or--it's the dying thoughts of an unnamed post-punk, post-gender existentialist youth on a suicide trip. Milligan's writing is amazing if occasionally absurd. Much of it reads like Tim Leary trapped in the semantic universe of an Indian restaurant menu.

Once again, it's the interaction between the writing and the illustration that provides such a lush and unique means of expressing the psychedelic experience. To bring the world of Rogan Gosh to life, artist Brendan McCarthy mined his own childhood obsession with the Amar Chitra Katha tradition of Indian comic books--cross-wiring that with the electric offspring of punk-rock pop art to produce a lurching, spiral play of hyper-color lotuses, sitar-rayguns, corridors of endless uncertainty, ashrams of the absolute, and the dead-end sprawl of South London.

A psychedelic classic from the early 1990s which deserves to be better known, Rogan Gosh combines a tryptamine-style romp through transpersonal existentialism with the neon-cartoon fireworks of a night out on high-quality phenethylamines--a bizarro cultural mash-up pulled off with wit and weirdness.

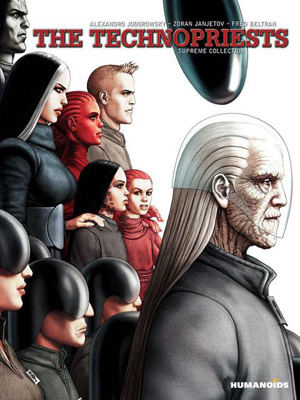

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a profoundly strange and intensely prolific individual, having put in solid time as a filmmaker, actor, spiritual teacher, ceremonial psycho-therapist, international expert on Tarot symbolism and, yes, comic book author. Probably best known for his films, including cult classics such as The Holy Mountain or acid Western epic weird-fest El Topo, Jodorowsky is also somewhat infamous for having tried and failed to make the first cinematic adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune. Considering that he planned on casting Salvador Dalí as Emperor of the Known Universe and wanted to commission Pink Floyd to do the film score, it's little wonder the project went down in expensive flames. Jodorowsky had also almost completely rewritten the sci-fi classic, recasting it as his own epic of transhuman visionary mythology bearing slim resemblance to the original.

When the Dune project imploded, Jodorowsky recycled his voluminous additional material into a triptych of comic book epics, of which The Technopriests is one part. The story combines influences from Gnostic Christianity, technopaganism, and visionary shamanism fed through the wormhole of space-opera superhero comics. It follows the adventures and education of "the Albino", a prophesied individual who must pass a variety of tests and penetrate various realms of existence in his quest for the power to lead humanity towards a society in which "healthy human relationships will be valued more highly than scientific advances".

With illustrations by Janjetov and brain-melting color by Beltran, The Technopriests is an eye-popping visual feast. Jodorowsky has been quoted as saying, "I ask of film what most North Americans ask of psychedelic drugs". The same would seem to be true of his work in comics. Indeed, in collaboration with Janjetov and Beltran, he brings worlds to life that would be impossible to film, even with today's CGI wizardry.

All the same, The Technopriests might best be appreciated as a predominantly visual experience. To call the dialogue "wooden" would be charitable, and there's hardly a character in the series who is anything less than a cardboard cut-out of mythic caricature. Additionally, the writing is almost completely lacking in humor. As humor is often the best and sometimes the only guide to states of altered perception, it seems like a psychedelic super-myth that isn't also funny is going to be lacking something. That said, The Technopriests is hands down one of the most gorgeous, mind-boggling examples of visionary narrative art available in any medium.

Furthermore, comic book superheroes are the closest thing contemporary culture has to living mythology, and those with pretensions to modern shamanism will tend to share traits with them. Ever since Ken Kesey began dressing up as his childhood hero, Captain Marvel, and encouraging his entourage to follow suit, the counterculture has continually reenacted the primal superhero traditions of outrageous costumes, taking on a totemic moniker, and cultivating the use of unusual abilities and extraordinary perceptions.

Here are some gems from the field of sequential visual art that focus on the exploration of alternative consciousness.

|

Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery #

by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely (DC Comics, 1996/2012)Don't let the leopard-print short-shorts fool you! Four-part comic book miniseries Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery (reprinted at long last in a handsome hardcover "deluxe" edition) is one of the most sophisticated representations of a drug trip ever written or drawn.

In a world on the brink of collapse, the last of the comic book superheroes--a half-naked cartoon strongman with psychic muscles struggles to solve the mystery of his long-vanished comrade's uncanny disappearance.

At the same time in an alternate reality, an unnamed rock singer is dying of a drug overdose in the rain. He's taken everything in the house, including quite a bit of LSD, and he's talking on a mobile phone to the unseen voice on the other end of a suicide prevention hotline. All he wants to talk about are comic books.

Meanwhile, in a third version of reality, a legion of all-powerful super-beings faced with inescapable annihilation devise a plan to survive death by projecting themselves into another universe as fictional characters.

Naturally, as the story progresses the walls between worlds begin to break down, culminating in collision with Total Reality and emotional catharsis in which there are "no more barriers between the real and the imaginary". If the world of psychedelic comic books dished out awards, Flex Mentallo would win "Best Comic Book Depiction of an Acid Trip" and "Best Narrative Depiction of Successful Psychedelic Therapy". Insofar as Flex Mentallo is about the use of non-ordinary states of consciousness to heal psychic trauma and transmute pain and fear into wonder, it is a story about psychedelic psychotherapy. Insofar as the structure of the miniseries mirrors and discusses the history of superhero comic books, Flex Mentallo is, well... about comic books.

For years Scottish author Grant Morrison has been using the medium of superhero comics to saturate his readership with an all-out assault on ordinary reality. His comics read like catalogs of ultra-hip esoterica and cutting-edge visionary speculation. Additionally, Frank Quitely's illustrations for Flex Mentallo are the clearest, most precise realizations of fantastic reality since Winsor McKay's Little Nemo in Slumberland. Together they cut an astounding swath across the limits of what is conventionally possible to represent, telling a story that's both formally intriguing and genuinely moving.

|

Rogan Gosh: Star of the East #

by Brendan McCarthy and Peter Milligan (Vertigo/DC Comics, 1994; first serialized in Revolver 1-6, Fleetway, 1990)Turn off your mind, relax and float downstream... into the sitar-fantastic surrealist wonderland of Rogan Gosh, where multi-cephalic Hindu gods, karma-surfing superheroes and long-dead Orientalist writers crash headlong into the bleak drizzle of London suburbia.

Rogan Gosh, written by UK comic book bad-boy Peter Milligan, is either the story of the eponymous "Karmanaut" in his struggle to free himself from the illusionary machinations of the villainous Soma Swami--or--it's what happens to curry-house waiter Raju and boorish lout Dean after the goddess Kali rips their heads off--or--it's the opium dream of a disgraced Rudyard Kipling--or--it's the dying thoughts of an unnamed post-punk, post-gender existentialist youth on a suicide trip. Milligan's writing is amazing if occasionally absurd. Much of it reads like Tim Leary trapped in the semantic universe of an Indian restaurant menu.

Once again, it's the interaction between the writing and the illustration that provides such a lush and unique means of expressing the psychedelic experience. To bring the world of Rogan Gosh to life, artist Brendan McCarthy mined his own childhood obsession with the Amar Chitra Katha tradition of Indian comic books--cross-wiring that with the electric offspring of punk-rock pop art to produce a lurching, spiral play of hyper-color lotuses, sitar-rayguns, corridors of endless uncertainty, ashrams of the absolute, and the dead-end sprawl of South London.

A psychedelic classic from the early 1990s which deserves to be better known, Rogan Gosh combines a tryptamine-style romp through transpersonal existentialism with the neon-cartoon fireworks of a night out on high-quality phenethylamines--a bizarro cultural mash-up pulled off with wit and weirdness.

|

The Technopriests #

by Alejandro Jodorowsky, Zoran Janjetov, and Fred Beltran (Humanoids/DC Comics, 2004/2011)Alejandro Jodorowsky is a profoundly strange and intensely prolific individual, having put in solid time as a filmmaker, actor, spiritual teacher, ceremonial psycho-therapist, international expert on Tarot symbolism and, yes, comic book author. Probably best known for his films, including cult classics such as The Holy Mountain or acid Western epic weird-fest El Topo, Jodorowsky is also somewhat infamous for having tried and failed to make the first cinematic adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune. Considering that he planned on casting Salvador Dalí as Emperor of the Known Universe and wanted to commission Pink Floyd to do the film score, it's little wonder the project went down in expensive flames. Jodorowsky had also almost completely rewritten the sci-fi classic, recasting it as his own epic of transhuman visionary mythology bearing slim resemblance to the original.

When the Dune project imploded, Jodorowsky recycled his voluminous additional material into a triptych of comic book epics, of which The Technopriests is one part. The story combines influences from Gnostic Christianity, technopaganism, and visionary shamanism fed through the wormhole of space-opera superhero comics. It follows the adventures and education of "the Albino", a prophesied individual who must pass a variety of tests and penetrate various realms of existence in his quest for the power to lead humanity towards a society in which "healthy human relationships will be valued more highly than scientific advances".

With illustrations by Janjetov and brain-melting color by Beltran, The Technopriests is an eye-popping visual feast. Jodorowsky has been quoted as saying, "I ask of film what most North Americans ask of psychedelic drugs". The same would seem to be true of his work in comics. Indeed, in collaboration with Janjetov and Beltran, he brings worlds to life that would be impossible to film, even with today's CGI wizardry.

All the same, The Technopriests might best be appreciated as a predominantly visual experience. To call the dialogue "wooden" would be charitable, and there's hardly a character in the series who is anything less than a cardboard cut-out of mythic caricature. Additionally, the writing is almost completely lacking in humor. As humor is often the best and sometimes the only guide to states of altered perception, it seems like a psychedelic super-myth that isn't also funny is going to be lacking something. That said, The Technopriests is hands down one of the most gorgeous, mind-boggling examples of visionary narrative art available in any medium.