It’s tough to write novels about tripping really, really hard.

The trouble with words as a medium for relating the psychedelic experience is that for the most part a trip is experienced not through language but through affect—that is, through feelings, intensities, currents, charges, zones of unbearable pressure and limitless expansion, etc. Many an erstwhile young psychonaut has scribbled away into the evening with a shaky hand, trying to capture on a page the cloud-capped towers and gorgeous palaces of their vision before the whole insubstantial pageant fades away like fairy dross. What most people find however, come morning, is that the real gist of a psychedelic experience is seldom expressed through the choice of words, but rather resides ephemerally in the feeling and energy that for a time flows through words, resides in words, or as often as not inhabits the negative spaces between words. Yet the moment that flow stops, the words themselves tend to go dead on the page. Separated from the psychedelic experience itself, the language used to relate it is all too often left signifying, if not exactly nothing, then at least a whole lot less than had been hoped (as in: “I spent an hour and twenty-three minutes figuring out how to use a pen for this?”).

That said, for the most part the burden of this difficulty is born by those laboring to produce nonfiction accounts of their own experiences. What, however, might be the possibilities of psychedelic fiction? What can you do with invention and imagination that you can’t properly (or easily) do with what “actually” happened?

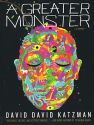

In this spirit, with his new novel A Greater Monster, author David David Katzman has taken the plunge and produced an exuberantly psychedelic narrative. His novel focuses on one rather miserable specimen of self-loathing yuppie excess who, for some reason, decides to eat the gelatinous pill handed to him in an alley by a homeless person and proceeds to experience total depersonalization. The story then follows the hallucinating yuppie’s point of view, to the point where it’s no longer clear that there is even really a “him” anymore—beyond that point the narrative jellies, coagulates, and liquefies into radically unstable characterization and wildly experimental typography.

Indeed, just as water can exist in its solid, liquid, or gas phases (or in various mixtures of these states), so too can literature be seen as existing in a number “phase states”. The “solid” phase in fiction would be something like dependable old-school Aristotelian narrative, which has a beginning, middle, and end, and is peopled with such entities as plots, characters, and a more-or-less consistent style of presentation. As literature approaches its “liquid” phase, the narrative point of view starts flickering through time, the protagonist’s identity becomes slippery and fluid, and the rules of the fictional universe begin changing anywhere from the chapter level (less liquid) to the paragraph level (more liquid). By the time fiction hits the “gas” state, the paragraph itself breaks apart and the standard printed sentence goes out the window. Here there be spiral sentences, text reading top to bottom or right to left, letters scattered across the page as if touched by invisible winds, words that leap lemming-like from their margins to pool incoherently at the bottom of the page, and so forth. [Note: this “gas” phase state in literature is also sometimes simply known as “poetry”.]

The narrative in A Greater Monster exists in (or rather, near) the “solid” state for no more than the first few dozen pages at best before careening out into space, spilling across the three hundred some odd pages that remain in a dizzying mixture of “liquid” (eek! I’m a lizard in a red space suit…no wait! I’m a talking bug…) and “gas” phases (get ready for a stroboscopically advancing letter “I” growing larger and larger till the page itself is transformed into tripartite columns of white and black). As such, reports relating the narrative content of the book are for the most part meaningless—save as a means by which to tantalize potential readers with promises that therein they may learn such things as how good manners are of lethal importance when taking tea with pirate skeletons; or that while you might be able to traverse the river of oblivion across a bridge formed by a man’s magically extruded penis, don’t expect coherent conversation with the magic-extending-penis man once you get to the other side.

After a certain point, A Greater Monster is no longer properly a “novel about a psychedelic experience”. A reader would have to be remarkably drug-naïve to accept that the narrative landscape is representative of any known style of drug trip. Instead, the novel turns into another genre altogether: the hallucinated fantasy picaresque. The hallucinated fantasy picaresque is generally either a satire or an allegory that takes the form of a free-wheeling trek across wounded galaxies of variably accelerating mutation, where point of view, mode of presentation, style of description, and dialect of narration all meet in a menacing clash of mash-up fairytale horrors (see: any movie made by Alejandro Jodorowsky in the 1970s).

Indeed, considering that the last “solid” narrative moment of the novel (somewhere around page 40) would seem to be the obscenely hallucinating narrator, gibbering mad on public transportation, getting his head caught in the closing doors of a city train…it may very well be that from that point on the story could be interpreted as some kind of Bardo experience—that is, a dead and disoriented soul’s journey through an afterlife landscape of karmic revelation and peril. (Although it’s certainly difficult to say.)

In one answer to the question posed above as to the possibilities of psychedelic fiction, while it will always be tricky to describe in words what a trip is like, it is much less tricky to describe what a trip ends up doing to the tripper, relating how they changed as a person through the course of it. Here fiction has a discernible edge. For one thing, through fiction you can really stress the potential results by setting the reader up to witness an extraordinary transformation in the protagonist.

In this respect however, evaluating the “tripper’s journey” represented in A Greater Monster may be tricky. For one thing, a significant baseline is never established for the protagonist. From the first page to the last I had no real idea who this person was or why he would act so suicidal. He grew up on a Native American reservation. He went to Harvard. He falls for women who find him repellant. Beyond that…?

In a book this out-there and trippy, there can be really only one “normal” dramatic question to ask, which is: Does the protagonist return from the great beyond (and if so, how is he or she changed)? Although it’s a spoiler, I feel compelled to caution prospective readers that the protagonist does not return at the end to anything like the reality/life/context/ego-delusion from which he began. As such, observing overall “change” in the character of the protagonist is tough, especially considering that often throughout the novel the protagonist changes into something new every few pages. It’s perfectly all right for the protagonist of this or any work to be a kind of disembodied subject experiencing a flowing succession of states of being. It’s important, however, to be able to discern whether or not these states are significant and specific.

Does A Greater Monster properly end? Is there an arc of development by which tensions are raised, held in suspense, and finally resolved? The answer in this case seems to be “maybe”. There are clues for sure—a passage here, a paragraph there—through which one might gain a foothold on what’s taken place and what’s at stake. But to do so a reader would have to do a very careful job of reading the whole thing. They’d have to maintain an extremely high level of focus from page to page and paragraph to paragraph, in order to catch what might be there. It’s a lot to ask, especially when the rewards for succeeding are not necessarily obvious.

Throughout the history of fiction, numerous gadfly-like types have pointed out that while the rules of “solid” Aristotelian drama are highly effective at being entertaining, they nevertheless have almost nothing to do with how life is actually lived. It duly describes the shortcuts the brain is inclined to take in the course of making meaning, but it’s got very little to do with how perception actually happens. As literature evolved into the twentieth century some very perceptive (and unsurprisingly peculiar) people pointed out that if you took the trouble to notice what cognition was really like, you’d discover that in order to actually represent consciousness as-it-happens, you’d practically need to start cutting up books with scissors and making collages out of the fragments.

Thus, for those who have absolutely no need to be coddled by conventional structures of entertainment or narrative closure, there is much of potential value in a work that happily shreds convention and consistency. Certain solid, significant truths can only be glimpsed in the midst of a delirium. However, as true and important as this fact may be, it’s almost always a mistake to assume that delirium alone is all it takes to produce those forms of truth. There has to be something there. Otherwise it’s like putting together a marvelous machine, simultaneously a microscope, a telescope, and a bundle of sci-fi scanners all in one, but then focusing it on a subject with nothing particularly special to say for itself.

Fatal error: Uncaught TypeError: count(): Argument #1 ($value) must be of type Countable|array, null given in /www/library/review/review.php:699 Stack trace: #0 {main} thrown in /www/library/review/review.php on line 699